When I quit Microsoft and joined the startup company in 2015, the first thing I learned is the concept of Microservices. It was touted as the future of software development, promising increased scalability, flexibility, and resilience. It seems everyone was jumping on the bandwagon, even the fledgling startups despite the inhere challenges involved. There was a joke about it:

There’s a thousand-line program here, we’ve got to break it to make it down into 10 hundred-line programs.

When I transitioned from the backend development world to the full-stack world in 2021, I found that all the buzz from the popular stack like Next.js, Prisma, and tRPC seems to be around monolithic, people were no longer talking about the microservices.

So, what happened? Is it because of the emergence of new trends and technologies or the reflection of Microservices itself after lessons learned? I would say both.

Reflection on Microservices

Why do you need microservices?

Our industry tends to focus on tech instead of the outcome. One should use microservices as a means to obtain the desired outcome rather than for the sake of using new technology.

Everything comes with a price, sometimes people forget the cost you need to pay when pursuing new trends in technology. Some typical costs include:

- Increased development complexity

- Exponential infrastructure costs

- Added organizational overhead

- Debugging challenges

Before diving into microservices, it’s important to consider the specific outcomes you hope to achieve. Ask yourself questions such as:

- Is there anything within the system that is scaling at a different rate than the rest of the system?

- Is there a part of the system that requires more frequent deployments than the rest of the system?

- Is there a part of the system that a single person, or a small team, that operates independently from the rest of the group?

Once you have clear answers to these questions, you can perform a cost-benefit analysis to determine whether microservices are truly necessary for you.

Monolith first

Marrin Flower is well-known as the father of Microservices. But are you aware of the below statements of his:

As I hear stories about teams using a microservices architecture, I’ve noticed a common pattern.

- Almost all the successful microservice stories have started with a monolith that got too big and was broken up

- Almost all the cases where I’ve heard of a system that was built as a microservice system from scratch, it has ended up in serious trouble.

This pattern has led many of my colleagues to argue that you shouldn’t start a new project with microservices, even if you’re sure your application will be big enough to make it worthwhile.

There are two reasons:

- When you begin a new application, how sure are you that it will be useful to your users? The best way to find out if a software idea is useful is to build a simplistic version of it and see how well it works out. During this first phase you need to prioritize speed (and thus cycle time for feedback), so the premium of microservices is a drag you should do without.

- The Microservices will only work well if you come up with good, stable boundaries between the services. But even experienced architects working in familiar domains have great difficulty getting boundaries right at the beginning. By building a monolith first, you can figure out what the right boundaries are, before a microservices design brushes a layer of treacle over them.

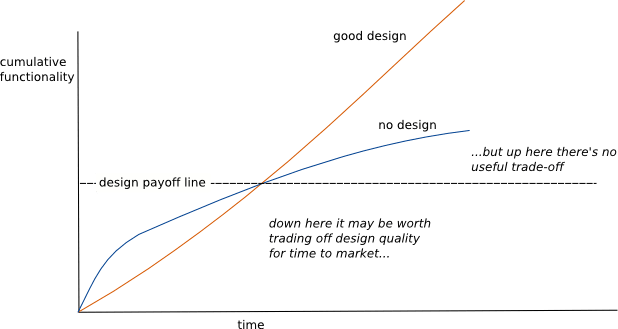

In conclusion, no architecture is often the best architecture in the early days of a system. Martin Flower’s Design Stamina Hypothesis also does a great job of illustrating this idea:

Monolithic can still scale

Advocates of microservices often argue that monolithic architecture cannot scale effectively beyond a certain point, but this notion is not necessarily true.

Since the beginning of 2006, Shopify was built as a monolithic application. It had grown to have

over 2.8 million lines of Ruby code and more than 500,000 commits. The certain point occurred at Shopify was 2016 when they see the increasing challenge of building and testing new features.

But you should know the financial status at that certain point of Shopify:

389 million revenue from serving 377k merchants

Moreover, they chose to pursue a Modular Monolith approach over Microservices. A modular monolith is a system where all of the code powers a single application and there are strictly enforced boundaries between different domains. While microservices emphasize the importance of boundaries, they do not necessarily have to be defined by service, but could also be implemented by module. This approach allows Shopify to enjoy the benefits of both monolithic and microservices architectures while minimizing their respective drawbacks.

To learn more about Shopify’s approach, you can read their detailed blog post on the topic.

Deconstructing the Monolith: Designing Software that Maximizes Developer Productivity

Distributed systems are hard

In essence, Microservices is a way of building distributed systems, which means they are not exempt from the inherent challenges of such systems.

One of the most significant hurdles is conducting transactions across multiple services. Although there are several methods for handling distributed transactions, such as the two-phase commit protocol, compensating transactions, event-driven architectures, and conflict-free replicated data types, none of them can provide the same simplicity that developers enjoy in a monolithic architecture with a database that offers transaction functionality. When things go wrong in a distributed system, data inconsistency can arise, which is perhaps the worst problem a developer wants to deal with.

New Technology

Serverless computing

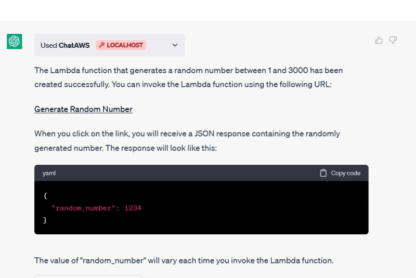

Simply from the name, you know it would be a challenger for Microservices. 😄 But I would say Serverless computing is actually an evolution of Microservices architecture instead of a replacement. Both approaches share the same goal of breaking down monolithic applications into smaller, more manageable components. However, while microservices typically involve deploying each service to a separate container or instance, serverless computing allows developers to focus solely on the code for individual functions, without worrying about the underlying infrastructure. After all, who wouldn’t want to get all the benefits promised by Microsevices including scalability, flexibility, and resilience but without worrying about server management or infrastructure?

Although it also has its own set of challenges, such as limited execution time for each function and potential vendor lock-in, Serverless computing continues to gain popularity and is considered one of the most promising emerging technologies, much like the heyday of Microservices.

Less code to write, fewer people needed

no matter what they tell you, it’s always a people problem.

In the book “The Mythical Man-Month” by Fred Brooks, he discusses how the number of people working on a software project can impact its scalability. Brooks famously states that “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later,” which has come to be known as Brooks’ Law.

Microservices can be treated as a solution for increasing scalability by splitting the large monolith into small pieces. Each piece would be taken care of by an individual team, in which people are more autonomous and more agile.

The recent emergence of new frameworks and toolkits has exceeded expectations in terms of quantity and speed. These modern tools can handle more and more tasks, freeing developers from writing as much code as before. For example:

- Using Next.js, you can build your entire web application in one framework and get SSR(Server Side Rendering) out of the box.

- Using tRPC, you don’t need to worry about defining the API either in RESTful or GraqphQL. You really have exactly the same experience of calling the local function when actually initialing the API call.

- Using Prisma, you can focus on building the application logic instead of dealing with database queries and migrations.

With these tools, a small team or even a single developer can create a high-quality, scalable application that can handle a large number of users and traffic. This is a significant shift from the past, where building complex applications often required a large team of developers. As a result, it postpones the inevitable scale point for teams to outgrow monolithic architecture.

You can read more in another post:

Complexity lies in the data layer

When it comes to scaling an application, it’s common to think about the complexity of the code. However, in reality, the underlying data layer is often the root cause of scaling issues.Traditionally, the data layer has been tightly coupled with the application code, and as the application grows, the relationships between data entities become increasingly complex and difficult to manage.

Prisma has made significant progress in reducing this complexity by introducing the schema file to define the data model for the application.

- the schema file serves as a single source of truth for the data model, making it easy for developers to understand and manage the application’s data layer.

- The schema file specifies the data types, relationships, and constraints of the data model explicitly, which can be easily modified and scaled as the application grows.

- The schema does a better job of communicating the intent and the understanding of the domain than the code does.

model User {

id Int @id @default(autoincrement())

createdAt DateTime @default(now())

email String @unique

name String?

role Role @default(USER)

posts Post[]

}

model Post {

id Int @id @default(autoincrement())

createdAt DateTime @default(now())

updatedAt DateTime @updatedAt

published Boolean @default(false)

title String @db.VarChar(255)

author User? @relation(fields: [authorId], references: [id])

authorId Int?

}

enum Role {

USER

ADMIN

}

The toolkit ZenStack we are building on top of the Prisma wants to go further along the path. We add the access policy layer in the schema file and automatically generate the safely guarded frontend data query libraries (hooks), OpenAPI, and tRPC routers for you:

model User {

id Int @id @default(autoincrement())

createdAt DateTime @default(now())

email String @unique

name String?

role Role @default(USER)

posts Post[]

//everyone can signup, and user profile is also publicly readable

@@allow('create,read', true)

// only the user can update or delete their own profile

@@allow('update,delete', auth() == this)

}

model Post {

id Int @id @default(autoincrement())

createdAt DateTime @default(now())

updatedAt DateTime @updatedAt

published Boolean @default(false)

title String @db.VarChar(255)

author User? @relation(fields: [authorId], references: [id])

authorId Int?

// author has full access

@@allow('all', auth() == author)

// ADMIN has full access

@@allow('all', auth().role == ADMIN)

// logged-in users can view published posts

@@allow('read', auth() != null && published)

}

enum Role {

USER

ADMIN

}

So by adopting it the majority of the backend work is to define the schema, which serves as the single source of truth for your business model. Additionally, we are considering the implementation of features in the schema, such as supporting the separation of database reading and writing. This will not only make scaling easier but also streamline the process of breaking the application into Microservices when you do reach a certain scale point in the future. Since the schema contains most of the necessary information, it will greatly simplify the process of transitioning to a Microservices architecture.